TV journalist Louis Theroux has interviewed everybody from porn stars to prisoners, recognized for deftly encouraging even probably the most combative or non-public interviewees to open up.

Theroux, who rose to fame together with his Weird Weekends collection 25 years in the past, was requested to ship this 12 months’s James MacTaggart Memorial lecture on the Edinburgh TV Festival, protecting the challenges going through broadcasters “in the multi-platform universe”.

He follows within the footsteps of historian David Olusoga, actress and producer Michaela Coel, and former BBC journalist Emily Maitlis – who hit out at her former employer when she gave the lecture in 2022.

In his speech, titled The Risk Of Not Taking Risks, Theroux made his case for the kind of journalism he’s recognized for, in an period when it would generally be simpler for TV bosses to play it protected.

The documentary-maker mirrored on his personal profession in addition to the present state of the BBC, with whom he has made numerous programmes.

“If I’m honest, I find the new world we are in troubling and exciting in roughly equal measure,” he advised his viewers of TV bosses and trade specialists…

“I am a contrarian and I appreciate seeing a complacent old guard discomfited by a grubby insurrectionary crowd of digital sans-culottes. But I also value truth and honesty and the rule of law.”

Here are 5 key factors from his speech to TV bosses:

Tackling tough topics in 2023

Dicussing altering attitudes to illustration and energy, Theroux stated: “We are, I’m happy to say, more thoughtful about representation, about who gets to tell what story, about power and privilege, about the need not to wantonly give offence. I am fully signed up to that agenda.

“But I ponder if there’s something else occurring as nicely. That the very laudable goals of not giving offence have created an environment of tension that generally results in much less assured, much less morally advanced filmmaking.

“And that the precepts of sensitivity have come into conflict with the words inscribed into the walls of New Broadcasting House, attributed to George Orwell: ‘If Liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.’

“And that in consequence programmes about extremists and intercourse employees and paedophiles may be more durable to get commissioned.”

‘The Tates and the Trumps’

Theroux warned of the hazard of trying away from extra excessive and provocative corners of the web out of fears of platforming hate and misinformation.

“With so much madness around, it’s tempting to ignore what’s out there. To not amplify it. Hope it goes away. To not platform it. Avoid the risk… I think that’s wrong.”

Theroux went on to reference former US president Donald Trump and controversial influencer Andrew Tate.

“Much of the new world epitomised by the Trumps and the Tates is based on the idea of monetising provocation. It relies on pushing people’s buttons to get our attention,” he stated. “Spreading sexism, racism, homophobia, sometimes dressing it up as irony, or comedy, while promoting a bigoted agenda. They do this both for both fun and profit.”

The debate surrounding the platforming of hate and misinformation “could be compared to debates around food and diet and the proper labelling of sugar and fat”, he stated.

“As with junk food, so too with junk facts. People can consume what they like but we could all do with a little help being nudged towards healthier choices, rather than having the information equivalent of chocolate bars on a two-for-one offer stacked in our eyeline every time we turn on our phones.

“I perceive all of this. I share the urge to change off all of the negativity. To flip one’s consideration elsewhere. To not feed the trolls. To by no means go wherever close to the trolls. I perceive the necessity to contemplate individuals’s wellbeing. To suppose by way of all of the attainable prejudices that could be contained in programmes. The influence of jokes and unconscious bias. All of the a number of methods wherein a TV present can do hurt.

“But it’s also true that there is a big difference between platforming and doing challenging journalism about controversial subjects.”

‘There was an urge to depict him in ever extra lurid phrases’

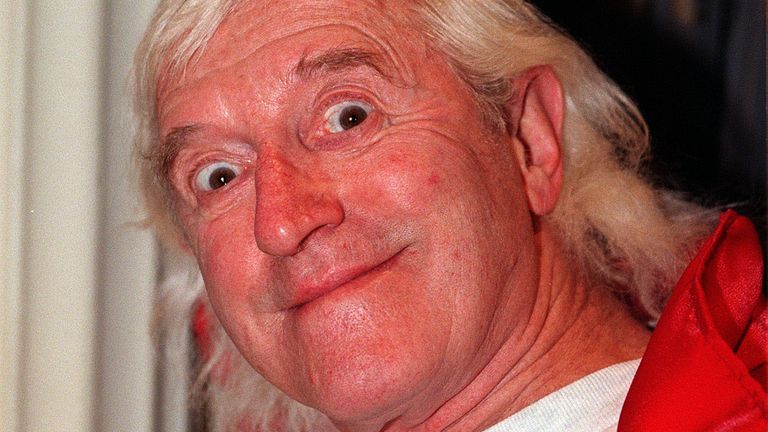

Theroux made two programmes about Jimmy Savile, and addressed these through the lecture. The first was in 2000, when he filmed with the DJ and TV fundraiser over 10 days, earlier than his crimes had been totally uncovered after his demise in 2011. The second was made in 2016, taking a look at how he escaped discover as a serial intercourse offender for thus lengthy.

The first “did not entail huge risk on my part”, Theroux stated, and on the time he was nervous primarily as a result of he was nervous Savile was “over the hill” and “past-it”.

The follow-up was very totally different. “I was among many examining their consciences to figure out if there was anything I could have done differently,” Theroux stated. “In making a second programme, I wanted to do justice to the scale of the harm he had caused. That, in itself, felt like a lot of pressure.”

However, he stated the “more worrying” subject was coping with unconfirmed allegations, comparable to claims Savile had “dismembered small children” and been concerned in “satanic rituals”.

“The outrage at his crimes was so convulsive, there was also an urge to depict them in ever more lurid terms,” he stated. “None of this had been credibly reported, but there were many who believed it might be true, and pushing back, making the case for a judicious weighing of the evidence, laid one open to charges of ‘minimising’.”

The “high-risk approach”, he stated, was truly “to take a considered and dispassionate look”, preserve “a forensic and questioning attitude” – and “not ignore the fact that for 40 years he charmed an audience of millions”.

On the BBC’s ‘no-win’ state of affairs

Theroux stated he understood why conventional TV makers may be afraid of taking dangers.

“From working so many years at the BBC, and still making programmes for the BBC, I see all-too-well the no-win situation it often finds itself in. Trying to anticipate the latest volleys of criticisms. Stampeded by this or that interest group. Avoiding offence.

“Often the criticisms come from its personal former workers, writing for privately owned newspapers whose proprietors can be all too blissful to see their competitors eradicated. And so there’s the temptation to put low, to play it protected, to keep away from the troublesome topics.

“But in avoiding those pinch points, the unresolved areas of culture where our anxieties and our painful dilemmas lie, we aren’t just failing to do our jobs, we are missing our greatest opportunities… and what after all is the alternative? Playing it safe. Following a formula. That may be a route to success for some. It never worked for me.”

Why he is not petrified of AI

Early in his speech, Theroux addressed deepfakes and synthetic intelligence (AI), saying Hollywood writers are hanging, “among other reasons, because of valid concerns over robots cannibalising their creativity”.

He expanded on this afterward, saying he doesn’t “overly worry about a takeover by AI” in the kind of programmes he makes. “I say this not as an expert on AI,” he stated, “but as an expert on humans.

“We’ve all seen the superb outcomes AI can produce. In a number of years it could possibly write a satisfactory sitcom or motion film. Or a MacTaggart. Maybe a wonderful one. Maybe one higher than this. But what it will not be capable of do is take dangers. Because threat entails hazard. And there is no hazard for machines. Risk entails actual feeling. The risk of humiliation, embarrassment, failure.

“Humans experience all those emotions and more… we connect over the frailties we have in common. We feed on the recognition of the common lot of human weakness. And when we recognise something real, there’s no substitute for it.”

Content Source: information.sky.com